Play It Again Bob: A Note on Dylan’s Variations

Original Post: Play It Again Bob - Timothy Hampton: Blog

Over the past year or so, I've had conversations about Bob Dylan's music with listeners in a variety of contexts. One topic always comes up: the way Dylan continually reinvents or reconfigures his songs in performance. "Why can't he play the songs the way they were written?" is the frequent question. I was even approached by a someone in a Dylan cover band, which performs re-creations of the original recordings. The answers to why Dylan messes with the songs, of course, are multiple: Dylan doesn't like to be bored. He can't pretend to be "sincere" in the ways that he was when he first composed some of these songs. He couldn't imitate those records if he wanted to, since his voice has changed dramatically in recent years. Most of these explanations, however, inevitably shade off into psychologizing guesswork. To try to work around this trap, I want here to offer a sketch of at least one intellectual framework that might explain part of what is going on. This is just a note, that builds on things I've tried to say elsewhere, but it might be of interest.

From his earliest days in Greenwich Village, as Dave van Ronk noted in his memoirs, Dylan has been interested in modern poetry. Central to his interests in the middle years of the 1960s, just as he was making his famous turn to "electric" music, was the French Symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud. It is Rimbaud who has given us the notion that the task of the poet is to be "absolutely modern" (that is, open to all experience in the moment) and the idea that modern poet must be a visionary. Most famous among Rimbaud's pronouncements is the phrase, "I is someone else." "Je est un autre." Many lovers of modern poetry and art, if they know no other French, know at least this phrase. It is often taken in psychological terms, to suggest that, no matter who we think we are, something of ourselves escapes our understanding. This is Rimbaud as Freudian analyst. Closer to the actual meaning of Rimbaud's formulation, however, is the simple sense that reality is multiple. The visionary poet lives in different worlds at the same time. One may be the world of what we accept as quotidian reality. But that may be only the least interesting among several alternatives. So, we each have multiple identities: "To each being it seemed to me that several other lives were due," says Rimbaud. He writes of visionary experiences in which he had conversations with "other" versions of people he was talking to. At one point a bourgeois family appeared to him as a pack of dogs. "Other lives," indeed.

Dylan's 1967 song "All Along the Watchtower" might be seen as an exploration of Rimbaud's insight. The lyric opens with conversation: "'There must be some way outta here'/ Said the Joker to the Thief." It is not clear who these characters are, in any referential frame of linguistic understanding. They appear to be two characters from a world of crime and carnival of the kind Dylan has peopled his songs with earlier in the decade—the "jugglers and the clowns" of "Like a Rolling Stone," the "geek" of "Ballad of a Thin Man," and so on. Here, they are set in opposition to two more obvious "straight" types, the "businessmen" and the "plowmen," who steal their riches. In this scenario, moral identities and nominal identities are reversed; the real thief is not the Thief; the real swindler is not the Joker. The juxtaposition between two easily recognizable types (we know what a plowman looks like; he has a plow) with two unrecognizable types (we don't know a thief when we see one, that's part of his being a thief) suggests the uncertain epistemological ground on which the song works.

This initial scenario expands into one of Rimbaud's parables of multiple identities in the third verse. Here the scene is recast as the drama of the "princes" who stand guard over their servants and treasure in their watchtower and wait for the "two riders" who approach menacingly to attack them. The third verse reverses the initial scenario. The swindlers who have stolen from the Joker and the Thief in the first verse are now threatened by two mauraders, come to take what they can. Everyone has taken on a new identity: businessmen have become princes, the Joker is a mysterious horseman. The song is powered and held together by the plot line, as those who have been exploited return to claim what is theirs. Yet the identities have changed. Each "I" is an "other." Each character lives in two realities, a reality of everyday exploitation in business, and a stark scene of impending battle over a medieval fortress. This is applied Rimbaud. "All Along the Watchtower" provides a working out of the shift from one referential frame to another. It offers a kind of poetics of allegory, as characters turn into other characters before our eyes—and as those new characters illuminate retroactively the initial cast of the song.

We might now apply this notion of multiple characters, of selves turning into other selves, to the songs themselves. That is, let's think of the songs themselves in the same way that Dylan seems to be asking us to think about the actors in "All Along the Watchtower." To each song, Rimbaud might say, several other lives were due. Take, for example, 1965's "Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues." "When you're lost in the rain in Juarez, and it's Eastertime, too," begins the lyric. There is no resurrection here, only a bad trip, bad weather, bad women, bad cops, bad experiences. It is a story of disorientation and misery, built on the I-IV-V chord changes familiar to listeners of electric, Chicago-style blues.

The title is interesting. The phrase "Just Like" opens up a space of mediation between this song and some other song that would be "Tom Thumb's Blues." These aren't Tom Thumb's adventures; they are "like" them. So, the singer, who is not "Tom Thumb," is humiliated in his adventures and left feeling small, miniaturized. So far so good. But the idea of "likeness" applies as well to the form of the song. This is not Tom Thumb's blues. It is "like" a blues. And, indeed, inside the rhythm of the song there lies another song. The chord voicings of the ringing electric guitar recall nothing so much as the parallel sixths and thirds that are conventional in Mexican music, in particular, in the form of the ranchera. We can think here of traditional Mariachi music of the type recorded by such Mexican stars as Vicente Fernández or Lola Beltrán. However, Dylan might just as well have heard these influences in the work of Texas musician Doug Sahm, for whom he expressed admiration early on. It's no accident that we are in Juarez. For inside of the "blues" of "Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues," there is another song, some version of a Mexican ranchera. And, indeed, if you push the tiniest bit of syncopation into the accompaniment, it becomes a tango.

Of course, Dylan doesn't emphasize the Mexican flavor of the song. Whereas some other artist might introduce Mariachi trumpets and violins, Dylan sticks to his basic sound. The other possibilities for the song lie latent within it, like the multiple identities of the Joker and the Thief in "All Along the Watchtower," or the dogs whom Rimbaud claims at one point to have seen where others saw a bourgeois family. This suggests at least one approach to Dylan's endless reinvention of his songs. The point isn't simply personal idiosyncrasy, or perversity, or a desire to annoy the listener. Rather, it involves an exploration of the multiple possibilities latent in each creation and each moment of creation. Indeed, it would be remiss of him not to explore these songs as much as he can--to see if "Don't Think Twice" can be done as a samba, or if "Idiot Wind" can be sung in a new key. New horizons may reveal themselves. Or they may not. But not to try to glimpse them is, in a sense, not to keep faith with the promise of modernity.

After History, Spirit: What It's Like to Listen to Rough and Rowdy Ways

Original Post: After History, Spirit - Timothy Hampton: Blog

Bob Dylan's new album Rough and Rowdy Ways is an exceptionally unified work. It has an internal logic, which unfolds as it goes. It is about the role of spirit and imagination in a landscape where history and myth have failed. To understand how this works, we need to look, not only at what the songs say, but, as I will do here, at what they do.

In recent years, Dylan's persona seems to have fallen into place. Whereas earlier in his career he changed looks every several years, his performances in the past decade or have featured him with the same flat brimmed hat, moustache, and Hank Williams suit. Having beaten his critics into submission, Dylan gives an impression in these songs that he grasps the fact that most of his listeners are actually on his side, and welcome what he is doing. This means that the "ways" of the album title are at once events (things I've done), manners (ways of living), and directions for life (roadmaps). Gone is the fragmented vision of much of Dylan's turn-of-the-century work (Time Out of Mind (1997), "Love and Theft" (2001), and Modern Times (2006)), in which we seemed to be stuck in the ruins of a national culture, suffering the consequences of decades of economic warfare, racist violence, and historical amnesia. The songs on Rough and Rowdy Ways are about working out approaches—to living, being, seeing. In this sense it is a strangely optimistic and even spiritual record.

The poetic possibilities made available by this approach are evident from the opening songs. He starts with Walt Whitman's famous line, "I contain multitudes." The multiplicity of the self is a long-standing Dylan preoccupation. After all, his 1970 album Self-Portrait was not autobiographical, but featured a set of songs by other people--a multitude of alter egos. Here, he makes the idea of a capacious self the main theme. He opens Whitman up, applying his famous line to the dignities and indignities of everyday life: "I drive fast cars, I eat fast foods." The sublime and the ridiculous come together in ways that Whitman, living in a pre-MacDonald's world, could not have imagined. The opening exploration of the question of selfhood is expanded in the second cut, "False Prophet," a blues about the self as a tool of power. The narrator is an impressive character--part con-man, part boaster, part magician. But no matter how threatening or exaggerated the claims of this persona, the song traces out an ethical path (a "rowdy way") through a world of thieves. Instead of condemning or preaching at the corrupt figures around him ("false-hearted judges," "masters of war"), as a younger Dylan might have done, he simply knocks them into line with his own power: "I'll marry you to a ball and chain."

Several of the songs are built on the conceit of taking a metaphor or a cliché image literally. "My Own Version of You" might seem to suggest some songwriting cliché about love and fantasy: "Venus, make her fair/A lovely girl with sunlight in her hair," sang Frankie Avalon in 1959. "Got a lock of hair and a piece of bone/And made a walkin', talkin', honeycomb," sang Jimmie Rodgers in 1957. Yet here, as in "Multitudes," the conceit is literalized. "My Own Version of You" is not an erotic fantasy about a dream girl. He really does want to construct someone; the narrator claims to be a kind of Dr. Frankenstein, who is going to make a human being from scratch. That design makes it possible for him to evoke both the wonders and dangers of our fallen life. The song ends with Dylan's narrator releasing his new invention into the world, a world of "laughter. . .and tears."

If I place an ellipsis in the middle of the cited lyric here, it is because moments of hesitation, where the singer stops, are important in these songs. Dylan frequently uses short phrases that alternate with musical interludes. The interludes break up semantic units or pairs of lines. He draws on sets of phrases or loaded words that are often paired in conversational speech or more conventional songwriting. When he says, "I'm first among equals," the listener knows that he's going to follow it with, "second to none." When he says, "I don't care what I drink," you know he's going to follow it with "I don't care what I eat." These lyrics are composed of brief phrases, punctuated by pauses in which the musical accompaniment takes over: "I've looked at nothing here/or there/Looked at nothing near/. . . .(pause) or far."

This ellipitical approach generates a game of tension and release. A phrase is begun and set of terms is hinted at. Then Dylan falls silent as the music plays, before he finishes the thought. In many cases this technique is built on rhyme effects. So, for example, in "Goodbye Jimmy Reed," we hear: "For thine is the kingdom/The power and the glory/Go tell it on the mountain/Go tell the real story." No one paying attention can fail to realize, long before we get there, that "glory" (followed by "tell it on the mountain," for heaven's sake) is going be rhymed with "story." In other words, Dylan is telegraphing his rhymes, letting us know before we get to them how they will stack up. He's not confounding us, as he might have done earlier in his career ("he just smoked my eyelids/and punched my cigarette"); he's releasing the tension and bringing things to a temporary moment of closure through rhyme and diction.

The effect of this lyrical and performative approach is a sense of open composition. In many of Dylan's earlier songs words pour out and over the listener with rapidity that is often surprising and exhilarating. Here, by contrast, Dylan is playing with banal everyday expressions ("I just know what I know"; "It is what it is") which let his listeners into the space of the song. He sings a part of a rhyming couplet, then we wait, along with him, as the band plays a phrase, and we anticipate the obvious and prepared-for rhyme that will close the couplet. We know when we hear "glory" that "story" can't be far behind; "stars" will certainly generate "guitars." When we hear, "turn your back," we wait for "look back." We sense that "Got a mind to ramble" will be followed by "Got a mind to roam." "Turn back the years." How? "Do it with laughter" (wait for it) "Do it with tears."

My point here is that the openness in the diction and delivery of the songs is of a piece with their thematic content. These are songs about making worlds, about inventing oneself, about righting oneself, about making a world out of bits of found material. Dylan is doing just that with language and sound: "I paint landscapes/I paint nudes/I contain multitudes." And he includes us in the process by giving us bits of information in short phrases, waiting a bit, then satisfying or influencing our expectation, sometimes with obvious words, sometimes with less obvious words. Either way, the songs breathe as Dylan breathes, and as we breathe with him. "What are you looking at?" he writes, "There's nothing here to see/ just a cool breeze that's encircling me."

Thus the songs are characterized by two interesting features. The first, as I've noted, is the way they take metaphors about selfhood and power and make them literal: "You wonder what Walt Whitman means by 'I contain multitudes'? Well, pay attention, and I'll try to apply the idea to a list of examples." This makes it possible for Dylan to study the relationship between the violent world of physical desire and power, on the one hand, and the world of imagination and spirit, on the other. The second feature I would underline is the way he deploys a kind of loose diction--brief lines, interspersed with pauses, common phrases that follow easily from each other. Like the singer, the songs stop to "breathe." The rhythms of breath that are the stuff of life (especially in pandemic times) are built into their very structure.

In this way the album unfolds logically, from self to society, from individual breath to collective spirit. It takes us from the self-focused "I Contain Multitudes" to the grand finale, the magisterial collective vision of "Murder Most Foul" that ends the record. Dylan prepares us for the final song with the lovely prayer, "Mother of Muses," and the beautiful fantasy, "Key West (Philosopher Pirate)." This last song reworks ideas set forward in 1997's "Highlands," about a man imagining an escape from this world. Yet the new song expands the conceit by interweaving the fantasy of escape with a specific geographical reference to Florida (more literalization) and an evocation of a musical phenomenon, the pirate radio station ("Coming out of Luxembourg and Budapest") that is beyond geography and can sing to the entire earth.

This pairing of geography and music becomes central to the final song, "Murder Most Foul." In the last tune, the implicit experience of community, of listening together, that has marked the structure of the diction and performance, now becomes explicit, part of the story. We move from personal identity, in the first song, to national crisis, in the last. Moreover, Dylan's account of the murder of JFK is above all an account of the consequences of that event for our national spirit: "The soul of a nation been torn away," sings Dylan. In the last tune, the hesitations and pauses in the singer's diction are gone, as the story unspools in long lines, like a passage from Milton's Paradise Lost. Having hesitated and offered brief bits of information in the earlier songs, Dylan now takes a deep breath decides to "tell the real story," as he urges Jimmy Reed to do earlier on. That story is a story about spirit, as is fitting for a song that takes its title from Shakespeare's Hamlet, the ultimate ghost story. It asks what happens to Kennedy's "soul" after he dies: "For the past fifty years they been searchin' for that." Dylan's claim is that Kennedy's spirit circulates in the music of the country, in a music that can console and heal, but that is also wounded and haunted, like the country itself. The song, like "Key West," is in part a celebration of radio, the medium of ghostly voices. And here Dylan's play with personal identity and pronouns is also exploded, as the "I" of the song shifts between the dying president and the commentator. I contain multitudes, indeed.

It is unclear to me whether the opening line of "Murder Most Foul"--"Twas a dark day in Dallas, November '63"--is supposed to evoke Joni Mitchell's powerful ballad of generational disillusionment and friendly counsel: "The last time I saw Richard was Detroit in '68." Either way, the resonance is meaningful. Mitchell's song closes her 1971 masterpiece Blue, just as Dylan's song closes Rough and Rowdy Ways. Blue is certainly one of the most self-absorbed recordings ever made. It is all about "I." Rough and Rowdy Ways, by contrast, takes us from an "I" that already contains "multitudes" to a parable of national tragedy. It offers a series of recordings that are set after historical tragedy and personal disappointment, after the events narrated by historians and epic poets. It explores the movement of spirit--across bodies, across time. It carries radio waves and warm breezes, breath, soul.

Murder Most Foul and the Haunting of America

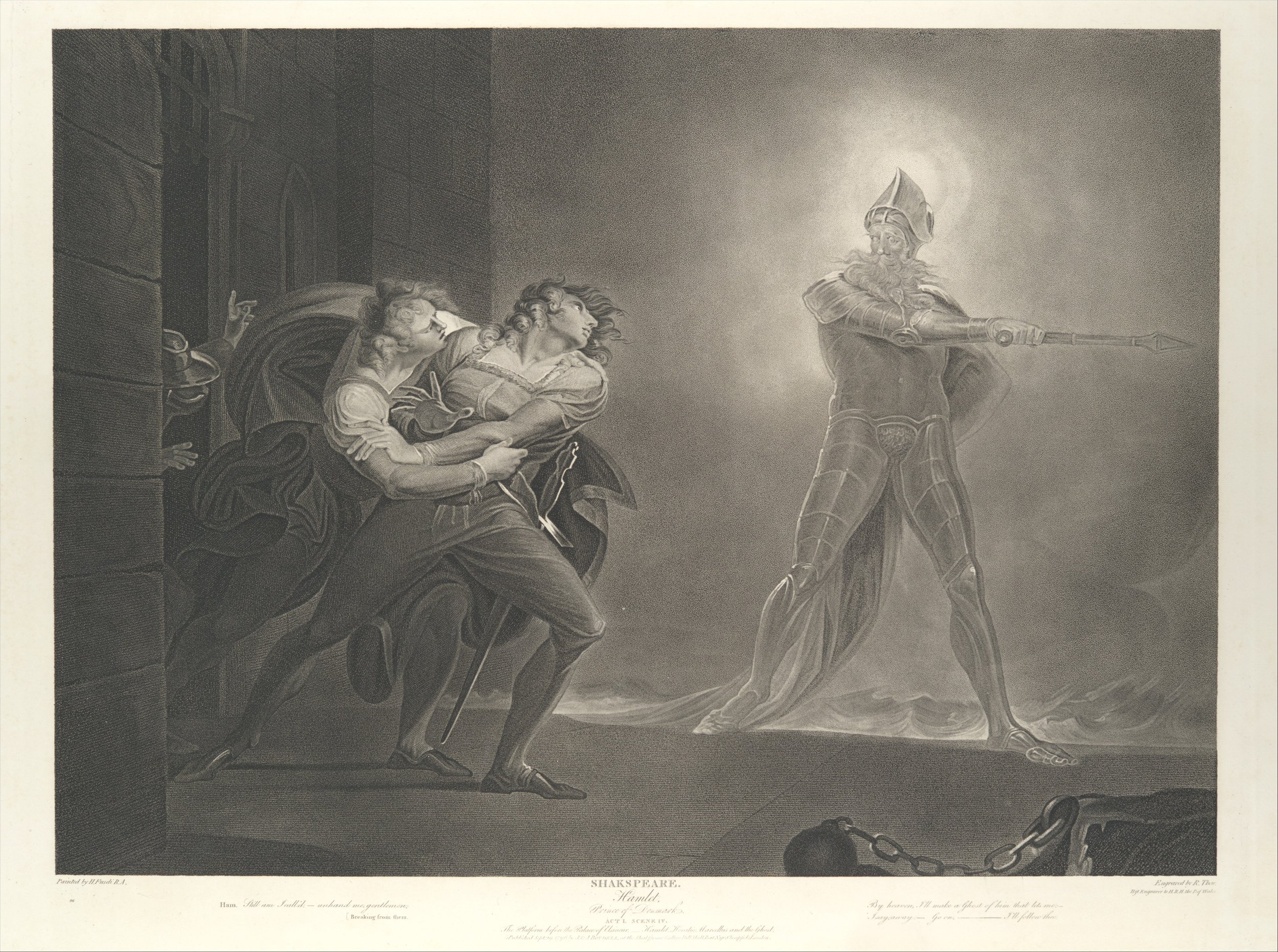

Hamlet, Horatio, Marcellus and the Ghost (Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 4) by Robert Threw

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

"Murder Most Foul" and the Haunting of America

"Play it! You played it for her, you can play it for me. If she can stand it, I can."

-Rick, to Sam, in Casablanca

One of the struggles of American literature in new century has been to grasp the totality, not merely of spiritual and moral changes in daily life, but of the very range of events that have overtaken us. The proliferation of media, the speed of the "news cycle," and the churning production of new forms of celebrity make up the chaotic backdrop to what used to be understood as "events"—major political changes, economic crises, floods, and plagues. At one level, this has always been a problem of American literature. But in earlier, less complicated moments, artists were able to grasp the larger fabric of American life through small flakes of experience which gestured--allegorically, as it were--to the larger catastrophes of our national life. The paranoid communities of Pynchon, the boxcar dramas of Jimmie Rodgers, the tangled but discrete "cases" of Raymond Chandler, all reflect beyond themselves onto the guilt, corruption, and greed that power our national political "progress" and economic "growth."

Bob Dylan has worked, across his career, to engage and represent the bloody complexity of American identity and life. Many of his songs from the mid-1960s— "Desolation Row," "It's Alright Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)," "Stuck Inside of Mobile," and so on—confronted the glitter and buzz of American life through a kind of visionary technique. The disjointed nature of much of Dylan's work during the 1960s uses the very form of the lyric to evoke the chaos of daily life while whittling it down into digestible bits. Waves of information swirled around and through those songs, which in turn bestowed meaning on them through the structuring presence of the singer. It was as if simply registering the sweep of the news and spitting it back as a set of images (Einstein disguised as Robin Hood, the President of the United States standing naked, and so on), could provide a cognitive point of reference from which we could make sense of things. The song became a set of images to which we could return to develop a kind of mental map of daily life. When we hear the opening of Highway 61--"God said to Abraham, 'Kill me a son'/ Abe said, 'Man, you must be putting me on!'"—we suddenly grasp that behind the fog of patriotism the fiasco of the draft and Vietnam is not a story of national defense, but a story of generational sacrifice, with God as a Mafia thug and Abraham a terrified parent, uncertain of whether to beg or run. It's all there, in one brief image and one narrative slice.

In the years since his visionary 1960s work, Dylan has turned to a variety of narrative forms to represent the sweep of national history. 1983's "Blind Willie McTell" drew on the traditions of epic poetry to offer a bleak unmasking of the racism that both infects the country and powers one of its greatest artistic traditions, the tradition of the blues. 1986's "Brownsville Girl," written with Sam Shepherd, offered a post-modern story-within-a-story to explore the erosion of courage and fake virtue. And now comes "Murder Most Foul," the seventeen-minute song released in late March 2020, in the midst of the Corona Virus Pandemic, against the backdrop of Donald Trump's daily flood of lies and insults from the house where Lincoln, Roosevelt, and Kennedy slept.

"Murder Most Foul" is about the assassination of JFK. But it is also about what constitutes an event, and about how an event takes on meaning beyond itself. At still another level, it is about the haunting of America, about the role of spirit in the national life. The title comes from Shakespeare's Hamlet, where the ghost of old Hamlet tells his son of his death: "Murder most foul, as in the best it is" (that is, all murders are foul), but "this most foul, strange and unnatural" (because fratricide and in secret), must be avenged. So we are in the land of ghosts, of the death of the "king," as Dylan calls Kennedy at one point. The style of Dylan's song is of an incantation. The half-chanted vocal over piano chords and a bowed bass remains largely on a couple of notes. There is little melody to speak of, and the harmony only occasionally moves off of the tonic chord, to add a bit of drama by moving to the sub-dominant or dominant. It tells the story of how the death of Kennedy, possibly a plot by Southerners eager to put LBJ in power, was also the death of American purpose and direction. It matters not whether Kennedy was a good president or a bad one. His murder was most foul, and that event paved the way, in Dylan's mind, it would seem, for the process of long decay, the rootlessness and suspicion, that we have lived since then: "The Age of the Anti-Christ has only begun," he says at one point. The song jumps around in time and focus, imagining the president in conversation with his killers, Dylan ventriloquizes the president while his persona comments, lamenting what has happened, noticing the landmarks on the way to the hospital.

Dylan once reflected that old folk songs are still alive for him--that the story of John Hardy, who "carried a razor everyday" and killed him a man on the West Virginia line back in the nineteenth century feels to him like it could have happened yesterday. Part of Dylan's gift is to grasp and make legible what an event feels like, what it means, from the inside. He has done this repeatedly, in such songs as "Only a Pawn in Their Game" (1963), about the murder of Medgar Evers, and "Hurricane" (1976), about the framing of the boxer Ruben Carter. To take us into the heart of the Kennedy experience Dylan draws on two literary traditions, which he weaves together across the song. First, most obviously, the song draws on the tradition of the murder ballad. To be more precise, it mobilizes a sub-category of that genre. Whereas conventional murder ballads make legends out of small time killers (for example, Stagger Lee, who killed Billy de Lyons over a Stetson hat), here we have to do with the death of someone already famous and with the implications of that event. The event lives past its occurence. To resolve this narrative problem Dylan mobilizes the Gothic or ghostly aspect of the murder ballad tradition. The literary advantage of using ghosts, as Shakespeare knew, is that they are unbounded by time and space. Perhaps the most famous musical Gothic is Lefty Frizzell's 1959, "Long Black Veil," in which a woman haunts the grave of the lover who died to protect her reputation. But there are multiple songs in which characters defy time and space. We can think, for example, of the Civil War era ballad "Tom Dooley" (which Dylan mentions here), where the narrative is in both the third and the first person about someone about to be hung. Or of Marty Robbins's 1959 hit, "El Paso," in which, as in "Long Black Veil," the narrator appears to be dead as he tells his story. These are songs about being haunted, about the spirit that moves about or sticks around after the body is dead. This is what "Murder Most Foul" is about. As Dylan points out midway through the song, they mutilated Kennedy's body for science, but nobody ever found his soul.

The question of where that soul has gone is what Dylan explores in the long, second half of "Murder Most Foul." Soul returns as voice. Anyone who knows the story of the Kennedy murder knows how it was framed. It was framed by the voice of Walter Cronkite, the trusted news anchor for CBS, who guided Americans through the days of agony and mourning as the dead president was buried and the transition to LBJ's administration took place. Dylan has evoked Cronkite elsewhere, in the ironic 1976 adventure tale "Black Diamond Bay," which he wrote with Jacques Levy. There, in the last verse, the narrator is sitting at home, "watching old Cronkite on the seven o'clock news." He hears about a disaster and turns off the tube. In that song, the question of what is "an event" is quite clear. It's what's on the news. You can shut it out by turning it off. But you can't turn off the murder of JFK. And where we would expect the voice of Cronkite, we here find the voice of the famous Disc Jockey Wolfman Jack, whom Dylan calls forth—"Wolfman, O Wolfman," he intones--and from whom he requests music: "Play Oscar Peterson, play Stan Getz." "I am thy father's spirit,/Doom'd for a certain time to walk the night," said old Hamlet to his son. In a song about haunting, about the haunting of America, Wolfman Jack, the werewolf, is the fitting guide.

If the song is about a great "event" in history, we could recall as well the tradition of the historical novel, which is also at work here. In that tradition, as the literary critic Georgy Lukács noted, the narrative runs, not through the great personages of history, but through the viewpoint of ancillary figures who show us obliquely what great events mean. And so, here, it is through Wolfman Jack that we will understand the meaning of Kennedy's death. Thus, the last half of the song consists of Dylan's persona asking the wolfman for songs. "Play. . ," he begins at the start of the third verse. And for 11 minutes or so he unspools a list of songs, from "Dumbarton's Drums" (a traditional Scottish song, known in the Civil War era) to Stevie Nicks. And it is here that the form of the song mirrors its message. For it is the radio, the medium of Wolfman Jack, that sends out messages through the night. Radio offers us ghostly messages. It brings the voice of the Other, of the past, of echoes and memories that come to you when you least expect it. You don't even have to log in. Dylan grew up listening to late night radio blasted from the deep south up to Minnesota—blues, country, rockabilly. Dylan knows that radio is the medium of ghosts, and he suggests here that Wolfman Jack is the voice who can call up the ghosts of American identity. This is most appropriate, since Wolfman Jack made his name broadcasting from Mexico, via XERB, one of the legendary "Border Radio" super stations that purveyed popular music to the southwest and West Coast. The turn to Wolfman Jack is both the ghostly invocation—"Stay, speak!" says Hamlet to the ghost—and the modern American reinvention of the funeral dirge: "Beat the drum slowly, play the fife lowly," ran the old cowboy lament, "Streets of Laredo," which Dylan quoted in 1989's "Where Teardrops Fall." In this case, the Wolfman speaks from outside America, paradoxically giving the country its voice. The fact that it is a voice from Mexico who speaks above the crimes of southern white conservatives, determined to destroy, not only JFK, but his liberal brothers ("We'll get them, too"), gives the song a deep resonance in our own moment.

Around the turn of this century Dylan wrote several albums of songs that dealt with the idea of the ruin, the fragment, the broken shard. Songs such as "Tryin' to Get to Heaven," from 1997's Time out of Mind, "Mississippi," from 2001's "Love and Theft," and "Workingman's Blues #2," from 2006's Modern Times, offered stories of lost souls, exiles at home, abandoned people struggling to find their way in a bleak economy, cut off from the past, from community, from stability. Dylan evoked their struggles through a disjointed writing style, stuffed with citations of other songs, bits of text taken from books and poems, as if the present were a field of broken artifacts, slivers of meaning and value after which we must all grope in the dark. In "Murder Most Foul" he offers something similar, except now in sonic terms. He calls for bits of song. What is the "voice" that can guide America after Kennedy? It is the voice of our music, of the echoes the come from the radio across the border. And through those echoes the event of Kennedy's death resonates as well.

There is nothing nostalgic about Dylan's journey through American music. He is clear-eyed about the triumphs and follies of the directionless generation that came of age after Kennedy. He evokes the foolishness of the Age of Aquarius, the silliness of Woodstock, the tragedies of Altamont and Kent State, Beatlemania. His narrative persona assumes, at one point, the place of self-indulgent Boomers, and at one level the song is a rewriting of Don MacLean's nostalgic "American Pie." But Dylan is deeper and more capacious. Again and again he asks the Wolfman for music, everything from Charlie Parker to John Lee Hooker. Not classic rock and roll; not Springsteen or the Stones--rather, the blues, jazz, deep music, elegant music, Beethoven, Nat King Cole. Music becomes both the witness to American decline and the only thing that can keep the spirit of JFK alive. Our art is stained, but it is all we have. It is the vehicle of haunting and the evidence that we are a haunted people: "Seen the arrow on the doorpost/Saying this land is condemned," sang Dylan in "Blind Willie McTell." In that song, the voice of the great bluesman was seen as the alternative to the disaster of American history. Here, the violence of a single event resonates across a world of song, via shards of radio play, echoes, names, bits of sound.

Yet "Murder Most Foul" is not merely a celebration of the power of art. Like Hamlet, it is about how illusions and fictions seep into our very being. As we move toward the end of the song, the list of singers begins to alternate with fragments of everyday speech, with colloquial expressions: "Play all of that junk and all of that jazz." At every turn, the "historical" details of the assassination are mediated through cultural representations: "It's a nightmare on Elm Street," intones Dylan, recalling one of the streets down which Kennedy was driven in Dallas, framed through a reference to a slasher film. National horror and the fictions of horror are evoked in the same breath. "Hush, little children, you'll understand," he says after the murder, echoing the words of thousands of parents in 1963. Then he adds, "The Beatles are coming, they're gonna hold your hand." The juxtaposition suggests the paradox of the moment, as pop music appears where human consolation should be. And indeed, every evocation of beauty seems haunted by a shadow: "Play Misty for me," he says, making a request for a love song, while evoking the title of a movie about darkness and obsession. "Frankly, Miss Scarlett, I don't give a damn'" he adds, misquoting Gone With the Wind by blending the language of Rhett Butler (who says, "Frankly, my dear") with that of Scarlett's black servant. American phrases, bits of misheard cultural vernacular, now jostle for our attention in the mix. The point seems to be that events and their afterlives are intertwined and that song is the ghostly form through which we can make sense of where we have been. American phrases, bits of cultural vernacular, now jostle for our attention in the mist, not on the ramparts of Elisinore, but in the sun at Love Field. The point seems to be that when we are haunted we slip easily, almost imperceptibly, in and out of art, proverb, cliché. And as the song ends it names itself in the last line, taking its place in the canon but also welding Shakespeare's famous line onto an event in our own history, both personal and political. As "Highway 61" reupped the Bible for service in the present, now Hamlet speaks again. And by making it speak, the song reminds us that a great crime is still alive. The king could have died yesterday. Music both recalls the event and soothes our spirits. And henceforth, JFK's ghost lives on in all of these songs. To sing them is to be reminded of his soul (in all senses of that term), but also to be confronted with the fact that, in every song we sing, our country is scarred by his murder, by murder most foul.

Echoes of a Fantasy: The Cultural Politics of Bob Dylan's Rolling Thunder Revue

Original Post: Echoes of a Fantasy - Timothy Hampton: Blog

Tangled up in white: Bob Dylan during his 1975 tour, the subject of the new documentary 'The Rolling Thunder Revue.'

Ken Regan/Netflix

One more cup of coffee.

Music and film fans were treated in early June to the Netflix release of Martin Scorcese's new film about Bob Dylan's 1976 tour, the Rolling Thunder Revue. The film features documentary footage of Dylan and his band in electrifying concert performances. That footage is framed by a set of interviews with both actual tour participants and fake talking heads, who comment on the events. By blurring history and fiction the commentary cleverly packages the tour as both chaotic and yet still relevant; it's subtitled "A Bob Dylan Story." Yet the clash of illusion and reality was already an essential part of the tour and contributes to its political meaning--both then, in the year of the American bicentennial celebrations, and now, in the age of Trumpism and Fox News.

The Rolling Thunder Revue had Dylan traveling across New England, playing in small cities, Plymouth to Montreal. He was joined by a Who's Who of fellow singers, including Joan Baez, Roger McGuinn, and Joni Mitchell. The band included musicians such as the violinist Scarlet Rivera and the bassist Rob Stoner, who had made Dylan's recent album "Desire" such a sonic delight. The choice of New England mill towns for the tour seems to have had a kind of spiritual-political intention. "Why would he play some place so small?" asks one of the fans in Plymouth, midway through the film. It was an encounter with a semi-rural America that was being depleted by a changing economy. The contemporary resonances with Trump's claims to speak for a "real" America are, of course, unmistakable. But the illusion of freedom presented by the tour was already shot through with nostalgia. For the context for the tour is the cultural misery of the mid-1970s, when the the late-1960s hippie dream of freedom, funny clothes, and "the road," had been brought up short by the reality of the defeat in Vietnam, Watergate, and a slowing economy.

The sense that the tour is a fiction (Dylan as gypsy) that is unfolding against another fiction (the glitzy surface of the bicentennial celebrations) is replayed in the iconography of the shows. Dylan's floppy hat and white face-paint mimic the main character of Marcel Carné's 1945 film about the Paris theater world, "Children of Paradise," an art house favorite about the clash between reality and illusion. Carné's film would form a loose template for Dylan's own attempt to reshape the Rolling Thunder material in his 1978 film essay, "Renaldo and Clara." But he had been quoting Carné as early as 1975, when the lyric to "You're a Big Girl Now" had cited the heroine of the movie reproaching her lover, who cannot free himself from the fictions he has made about her identity, "Love is so simple." Dylan, in makeup and headgear, here mimics Carné's doomed character Baptiste, caught between the banal reality of family life and the romance of illicit passion--even as the singer's jeans, vest, and boots turn him into some version of Billy the Kid from a Hollywood western. He is both artiste and bandido, exotic yet American. His carnival company and the powerful, shouted, vocal performances remind the post-1960s audience that the "real" America was a utopian collective that could still take shape—at least on the stage. Life may not, in the end, have turned out to be a magical mystery tour for many of Dylan's listeners, but Dylan's show reinvented the audience's favorite stars, from Baez to McGuinn, as Children of Paradise in the American grain.

Paralleling the ambiguity of the spectacle were the new songs, taken mostly from 1975's "Blood on the Tracks" and 1976's "Desire." The first of these albums looks back to the 1960s, recasting that era's social unrest as a version of "On the Road." The mad journeys depicted in such songs as "Tangled Up in Blue" and "Idiot Wind" both reflected Jack Kerouac's beatniks and the later, less sublime, moment of hippie restlessness. Rolling Thunder reinvented these themes as a musical bus trip. Against the phony patriotism of the bicentennial events, Dylan's group was digging deep into the bloody recent history of a wounded country.

Yet these songs are offset by the songs from the recently released "Desire album," which form the heart of the set list in the film. These songs, co-written mostly with Jacques Levy, have everything to do with the politics of Rolling Thunder and of Scorcese's film. For the "Desire" album straddles the violent line of confrontation between dream and reality, fantasy and brutal fact. "Desire" features a set of narratives of wandering and romance--songs about the south seas, the Klondike gold fields, Mexico, gypsy camps. Dylan's stage act, with its gypsy flavor and exotic outfits, performs what the songs are about. Yet at the same time, for every tale of exotic beauty on "Desire" there is a tale of brutality or disillusionment, bringing us back to the desperation of the mid-1970s in the "real" America. Thus the mythical romance "Isis" ("a song about marriage," as Dylan says at one point) stands over against the domestic drama of "Sara," a tune written for Dylan's soon-to-be-ex-wife, begging her not to leave him. Similarly, the romanticism of "One More Cup of Coffee," which depicts a beautiful gypsy woman whose clan is ruled by a knife-wielding king, runs up against the brutal sociology of "Joey," a tune about a Mafia clan ruled by an "old man" and his sons. This confrontation of enchantment and disenchantment haunts the album and makes it particularly difficult to read. We find it again on "Mozambique," a tune about jet setters on the beach recorded at a moment when the the African country had just achieved independence from Portugal after a brutal ten-year war. And, of course, it is central to "Hurricane," Dylan's account of the framing of the boxer Ruben Carter for murder. (Carter appears in a contemporary interview wearing a wide-brimmed hat of his own, almost like a parody of Dylan's festooned Stetson from 1976). The fact that Carter's story unfolded in Paterson, New Jersey, the site of William Carlos Williams's American epic poem "Paterson," made the bicentennial background to "Hurricane" all the more cogent. No less important, the harmony and groove of the tune hark unmistakably to Dylan's own earlier hymn to poetry and art, "All Along the Watchtower" of 1967. That song, with its "Joker" and "Thief" pointing ahead to the circus-like atmosphere of Rolling Thunder and Desire, here runs up against the brutality of life in the streets. The allegorical medieval castle that ends the song--the site of the famous "Watchtower"--is swept away by the vision of what happens to real boxers, in real landscapes: "In Paterson, that's just the way things go," sings Dylan. "If you're black, you might as well not show upon the street."

The point here is that the play of fantasy and reality that shapes the Rolling Thunder Revue is part and parcel of both the moment of its creation (the glitzy surface of the Bicentennial overlaying the despair following the recent defeat in Vietnam) and the songs that make up the performances. Dylan is asking us to think about what happens to the dreams of American romance in a world of military disasters and framed boxers. His exotic persona--in white face, peering out from under the floppy hat--seems now like a heroic attempt to replace anomie with magic. The disillusionment of 1976 is sublimated into Dylan's gypsy identity, which labors to resolve violence and romance. That dialectical effort is, in turn, reworked forty years later, with Scorcese's introduction of phony talking heads and grandiose commentary. Halfway through the movie Michael Murphy turns up, pretending to be the fake politician he played on the "reality" TV series "Tanner '88." The implication is that in 1976 Dylan tapped into something "essential" in America--but that it can now only be delivered as a cinematic joke.

Every event in American history returns as show business at some point. Even when we try to think about the limits of illusion and romance we can only do so through the prism of yet another form of fiction. This American fact haunts the project of the film and the concert tour. It is condensed in a single detail that emblematizes the whole project. Near the end of the film we see Dylan visiting Ruben Carter in jail. Dylan is trying to raise support for a man who has been falsely imprisoned. This is the American echo of Emile Zola's accusation of the French government in the Dreyfus Affair--an instance of a great artist stepping up to defend the innocent. We are dealing with life and death here. It is serious business. And yet Dylan shows up for the meeting in his floppy buckaroo hat, adorned with flowers. He is never out of costume, even when someone else's life is on the line. The moment encapsulates the interplay between fantasy and reality, show biz and political violence, that the tour and the film both chronicle and struggle to resolve. Show biz, as always in America, wins out.